'Buddy Christ' Won't Improve Women's Pro Soccer In The United States

There's no such thing as capitalism that "protects" athletic workers

At this point, there are myriad possibilities for the future of the National Women’s Soccer League. However, the only real path to the environment that everyone involved says they want is the exact strategy that no one in any position to make decisions in the league is so far discussing publicly.

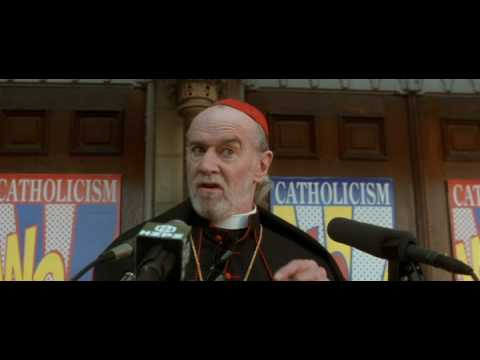

Private ownership of the league’s 12 franchises is what created the environment that has not only enabled exploitation in many forms but protected those who are/have benefitted from the exploitation of the league’s athletic workers. Just like how the Catholic Church sought to re-brand itself to try to distance itself from the abuse its edifices wrought in the movie Dogma, a “Buddy Christ” version of private ownership of clubs will only delay inevitable similar results. The bottom line is that there is no version of capitalism that doesn’t lead to worker exploitation because the system incentivizes that element.

"Buddy Christ” and NWSL ownership

The 1999 Kevin Smith-directed film debuted “Buddy Christ” with George Carlin playing Cardinal Glick to do the introduction. In the scene, he explains how the Catholic Church’s traditional depiction of its deity on a crucifix was “too depressing” and didn’t embody the “positive message” that the church wanted to portray to attract younger donors.

Buddy Christ has since appeared in other works Smith took part in. They include the Clerks and Jay & Silent Bob franchises. Various merchandise lines feature some Buddy Christ-branded elements as well. All in all, it’s pretty succinct social commentary.

History bears plenty of evidence of religious organizations adapting to the cultures they exist within. Like any other facet of society, they eventually face a choice: evolve or become obsolete. When faced with the choice of closing the doors to the Bible Barns because they’ve run out of ideas for recruiting adults willing to fund the grift and the faithful are no longer pumping out babies who they can indoctrinate in the religion before they are old enough to scrutinize the information being shoved down their throats or give ground on the hills they formerly would have died on, the former usually eventually always wins. There are lots of people who don’t want to give up their federal housing allowances, forfeit their tax-exempt status, and have to actually work for a living instead of just spouting off the sales pitch and watch the checks roll in.

In the same way, NWSL franchise owners enjoy the perks they receive from that status and bought in because they believe it will enrich them personally. The interests of athletic workers are diametrically opposed to that interest in principle, and eventually, one has to win out over the other.

Capitalism is the NWSL’s biggest problem

Capitalism is the driving interest behind the NWSL’s continual attempts to sweep any and every occasion that occurs which doesn’t sell itself off as a shining beacon of excellence. The overarching desire to protect power, privilege, and consolidate them further provides motivation for every form of abuse.

We’re all familiar with the issues that have plagued the league this year. However, it’s nothing new for 2021. As the recent reports about former Courage and Thorns head coach Paul Riley revealed, the exploitation has been ongoing for years. Over the years, that’s included deplorable working conditions that today extend to the league’s officiating crews.

Capitalism motivates franchise owners to not only hide the abuse of workers but take part in it by spending as little capital as possible to produce the product they are selling and make that as desirable as possible to consumers. That’s why most of the athletic laborers have to work side hustles and why the quality of the officiating during matches is so poor.

Having identified the problem, then, is there a way to introduce “compassionate capitalism” into the league? Would the league’s first collective bargaining agreements between club ownership and athletic workers plus other club staff and officials, resulting in a Buddy Christ-version of private ownership in the league, be sufficient to protect worker interests? There are several flaws with that approach.

A half-measure that will inevitably produce similar damage

We are able to look into the future with North American professional sports leagues that practice private ownership of members clubs that have robust player associations, officials unions, and histories of CBAs. By and large, the franchise owners continue exploiting athletic workers and do so with the blessing of governments because of employment law’s deference to CBA terms.

The NFL’s CBA, for example, is what has insulated NFL team owners from bearing any liability so far for how NFL franchises have addicted athletic workers to opioid painkillers. The intentional exclusion of “minor-league” baseball players from MLB’s CBA is what allows clubs in that league to exploit athletic workers with substandard wages and overbearing demands.

The problem with negotiating a CBA for workers in these enterprises is that it gives these franchise owners an entitlement they don’t naturally possess. It casts upon them ownership of the product, which are sporting events. In reality, the only thing these people own is rights for the various clubs and perhaps the connected facilities in some cases. The athletic labor necessary to produce the product is the exclusive property of the athletic workers.

Athletic workers do not need franchise owners. Consumers of the product will buy it regardless of how it is made available. If there is no labor, there is no product that gives the facilities and trademarks any value. No one is paying to simply sit inside SeatGeek Stadium for two hours or signing up for a Paramount+ subscription to watch Merritt Paulson talk about his ownership of the Portland Thorns FC name.

All the value is in the labor of the athletic workers and they thusly should control the product. The only path forward for an NWSL, or another similar fixture for women’s club professional soccer in North America, is worker ownership.

Dramatic transformation or abandonment is the best course forward

Unless those people who collectively currently own the rights to the league’s 12 franchises are willing to fully hand over control of those clubs to the NWSLPA and its members, the constituency of the PA should abandon the league and its franchises. There is nothing stopping the membership of the PA from on their own negotiating contracts with venues, broadcasters, officials, and sponsors for their own fixtures.

The value of their celebrity and talent is far greater than the value of the NWSL’s brand. Supporters will flock to the new fixture and follow the players in abandoning the NWSL and its clubs. Worker ownership will ensure that not only will all share equitably in the revenue the product produces but that there is no room for those who would exploit them.

Those who currently own shares in NWSL clubs could still be free to invest in the product if the players collectively would accept such funding. Investment does not necessitate control. If these owners are truly involved to push forward professional women’s soccer in North America and believed buying into the capitalist structure was the only way to do so, then nothing would change.

NWSL players have a choice and all the power. They can continue to subject themselves to exploitation done with a gentler touch – a Buddy Christ version of the current abusive system – or they can take full ownership of what already belongs to them anyway. If the NWSL chooses to not be a part of that, then good riddance.